So here it is:

Cheap, Trashy and Possibly Revolutionary: Comic Book Culture and Social Positioning

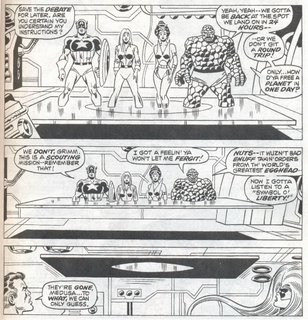

Comic books have a history of low cultural valuation, running along a line directly back to their pulp magazine, mass-product roots. It is a history to which they remain tethered, in spite of the work of countless critics, scholars, and serious cartoonists over the past few decades, and, frankly, because of some others. Superhero comic books (which represent the majority of comic books that have been published in the United States) in particular are primarily regarded as escapist power fantasies, for that is precisely what they are, though they are other things as well (it’s largely in how the reader uses them). Non-superhero comics tend to be the same way for the most part, drawing on crime-based power fantasies, science fiction-based power fantasies, horror-based power fantasies, etc. Those that are not power fantasies (at least in the obvious sense) are often self-consciously avoiding that label, and are therefore still in some ways defined by it. In any case, it is not difficult to see the connection between the low status of comic books among arts and letters, the type of fantasy material that most of the work published to date either represents or knowingly disavows, the means by which the work is produced and distributed, and the people who read, consume, and generate demand for more of the same.

Much effort has been made in recent years to elevate comic books in terms of their status among the mass media. From the industry side this has involved entry into bookstores (as opposed to only being available in specialty shops), an emphasis on single-volume publications or collected editions of previously published material and articles in major newspapers and magazines with the occasional appearance on a television news show or National Public Radio broadcast. Among participants in comic book fan culture, it has involved attempts to arrive at a consensus as to which comic books are great works, which decades represent the important eras, and which creators are making the most--and most important--contributions to the form of comics. Academically, it has resulted in volume after volume of apologetics, assuring us that yes, comic books--even superhero comic books--can and do have literary merit. This happens over and over again, and frequently involves the same comic books (Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, Maus, Jimmy Corrigan, Ghost World) being used as examples. Librarians, journalists, prose authors, film directors and scholars are all eager to tell us that while we may think of comic books as objects of trash culture, they really aren't.

But they also are. And as a complement to all of the new critical appreciation for certain comic books that “rise above” the regular garbage (which I think is a vital and important subject of its own), I am proposing that we look at the rest of it as well—that is, look at the trash as trash where necessary and see what it tells us about the culture as a whole, about the medium, about its creators, and about how the readers and fans are using the texts and participating in the formation of the culture. While the examination of important and pivotal work is valuable, I believe that to focus primarily on that work and how it is read to the exclusion of the vast body represented by everything else (that is, the trash) will also exclude the experiences and critical responses of the readers of everything else. Such an approach would erase from the scholarly view the contribution that those readers have made to the development of comic book culture and culture at large. It would also blind us to an examination of how readers have used the texts to position themselves within the comic culture, particularly as it relates to their positions in the culture at large. I want to include the reader and the fan in the emerging scholarship of comic books along with the examinations of the other aspects of comic book culture. Fan and reader activity on the internet has demonstrated that the readers are actively engaged with the texts and with the culture. They are also much more diverse than conventional wisdom suggests, as are their reading and participatory strategies. Through an examination of reader participation in comic book culture and the ways that it affects the creation of individual works and the industry as a whole, I hope to discover something about narrative and its relationship to the reader, and how the reader can use narrative to navigate culture, which in turn feeds the production of future narratives. I believe that the size, the history, the high level of reader participation, and the collective and ongoing authorship of the most popular and resonant narratives make comic book culture an ideal place to examine these effects.